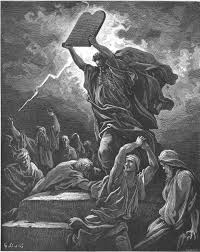

The beginnings of the modern system of criminal and civil law in Western Society can be traced back to the Law of Moses, given around 1300 BC. The Law of Moses (or “Torah”) is a biblical term first found in the Book of Joshua 8:31-32 where Joshua writes the Hebrew words of “Torat Moshe” (Law of Moses). The “Law of Moses” in Ancient Israel is distinguished from other legal codes in the ancient Near East by its reference to offense against a deity rather than against society. This compares with the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100-2050 BC), then the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), of which almost half concerns contract law. The content of the Law is spread among the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then reiterated and added to in Deuteronomy. This includes:

The beginnings of the modern system of criminal and civil law in Western Society can be traced back to the Law of Moses, given around 1300 BC. The Law of Moses (or “Torah”) is a biblical term first found in the Book of Joshua 8:31-32 where Joshua writes the Hebrew words of “Torat Moshe” (Law of Moses). The “Law of Moses” in Ancient Israel is distinguished from other legal codes in the ancient Near East by its reference to offense against a deity rather than against society. This compares with the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu (c. 2100-2050 BC), then the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), of which almost half concerns contract law. The content of the Law is spread among the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers, and then reiterated and added to in Deuteronomy. This includes:

- The Ten Commandments

- Moral laws – on murder, theft, honesty, adultery, etc.

- Social laws – on property, inheritance, marriage and divorce,

- Food laws – on what is clean and unclean, on cooking and storing food.

- Purity laws – on menstruation, seminal emissions, skin disease and mildew, etc.

- Feasts – the Day of Atonement, Passover, Feast of Tabernacles, Feast of Unleavened Bread, Feast of Weeks etc.

- Sacrifices and offerings – the sin offering, burnt offering, whole offering, heave offering, Passover sacrifice, meal offering, wave offering, peace offering, drink offering, thank offering, dough offering, incense offering, red heifer, scapegoat, first fruits, etc.

- Instructions for the priesthood and the high priest including tithes.

- Instructions regarding the Tabernacle, and which were later applied to the Temple in Jerusalem, including those concerning the Holy of Holies containing the Ark of the Covenant (in which were the tablets of the law, Aaron’s rod, the manna). Instructions and for the construction of various altars.

- Forward looking instructions for time when Israel would demand a king.

Jewish philosophers played a crucial role in the transmission of the concepts and ideas of ancient Greek philosophers to early Christian thinkers, thus influencing the development of Christian doctrine and theology. The earliest Jewish philosophers were those who applied philosophical inquiry to the tenets of their own faith, in order to provide a logical and intellectual explanation of the truth. Early Jewish scholars, well-acquainted with the ideas of Plato, Aristotle and Pythagoras, identified Moses as the teacher of the ancient Greek philosophers. Philo Judaeus (aka Philo of Alexandria 20 BC – 50 AD), one of the earliest Jewish philosophers and a founder of religious philosophy, attempted a synthesis of Judaism with Hellenistic philosophy and developed concepts, such as “Logos”, which became the foundation of Christian theology. (Jewish tradition was uninterested in philosophy at that time and did not preserve Philo’s thought; the Christian church preserved his writings because they mistakenly believed him to be a Christian.) Philo did not use philosophical reasoning to question Jewish truths, which he regarded as fixed and determinate, but to uphold them, and he discarded those aspects of Greek philosophy which did not conform to the Jewish faith. He reconciled biblical texts with philosophical truths by resorting to allegory, maintaining that a text could have several meanings according to the way in which it was read.

Saadia Gaon

Saadia Gaon (892-942) is considered one of the greatest of the early Jewish philosophers. His Emunoth ve-Deoth (the “Book of the Articles of Faith and Doctrines of Dogma”), completed in 933, was the first systematic presentation of the philosophical implications of Judaism. Gaon supported the rationality of the Jewish faith, with the restriction that reason must capitulate wherever it contradicts tradition. Jewish doctrines such as creation “ex nihilo” and the immortality of the individual soul therefore took precedence over Aristotle’s teachings along these lines.

Maimonides

Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon (1135 – 1204), known commonly by his Greek name Maimonides, was a Jewish scholar whose Guide for the Perplexed and philosophical introductions to sections of his commentaries on the Mishna exerted an important influence on the Scholastic philosophers. Maimonides believed the fundamental tenet of Scholasticism, that there can be no contradiction between the truths which God has revealed and the findings of the human mind in science and philosophy, by which he understood the science and philosophy of Aristotle. On some important points, however, he departed from the teachings of Aristotle, supporting the Jewish doctrine of creation ex nihilo,` and rejecting the Aristotelian doctrine that God’s provident care extends only to humanity in general, and not to the individual.

Maimonides was led by his admiration for the neo-Platonic commentators to maintain many doctrines which the Scholastics could not accept. He was an adherent of “negative theology,” maintaining that no positive attributes can be predicated to God, because referring to multiple attributes would compromise the unity of God. All anthropomorphic attributes, such as existence, life, power, will, knowledge – the usual positive attributes of God in the Kalâm – must be avoided in speaking of Him.

Joseph Albo

Joseph Albo, a Spanish rabbi and theologian of the fifteenth century, is known chiefly as the author of a work on the Jewish principles of faith, Ikkarim. Albo limited the fundamental Jewish principles of faith to three:

- The belief in the existence of God

- The belief in revelation

- The belief in divine justice, as related to the idea of immortality.

Albo criticized the opinions of his predecessors, but allowed a remarkable latitude of interpretation that would accommodate even the most theologically liberal Jews. Albo rejected the assumption that creation ex nihilo was an essential implication of the belief in God. Albo freely criticized Maimonides’ thirteen principles of belief and Crescas’ six principles.